| Marin Conservation League | 175 N. Redwood Dr., Ste. 135 | San Rafael CA 94903 | Tel 415.485.6257 | Fax 415.485.6259 Email Us. |

|

St.Vincent's / Silveira

A Brief History

(Note: The Marin Conservation League has no connection with Silveira Ranch or St. Vincent's. MCL has published this page because of public interest in these scenic and ecologically significant lands. Any specific questions about the properties should be directed to the property owners or the office of Damon Connolly, District One Supervisor.)

The Silveira Ranch and St. Vincent’s lands are customarily linked as one planning site because they adjoin one another, and they are the only remaining ranches in the Eastern City-centered Corridor of Marin County (Ranch lands along Hwy 101 north of Novato are in the Countywide Plan’s “Inland Rural Corridor”). The Silveira Ranch (pictured) still runs an active dairy operation.

St. Vincent’s gave up most of its agricultural production long ago but still harvests an oat-hay crop east of the railroad tracks. Its primary activity is to host a complex of educational and religious facilities, including the St. Vincent’s School for Boys. Long after all other dairy ranches in eastern Marin were sold off and developed, the future use of these two parcels has remained in contention. The properties are viewed as an essential community separator (between San Rafael and Ignacio) by some, and as an opportunity-site for infill development for affordable housing by others. MCL has long sought preservation of all or most of the two properties, and MCL representatives have participated for more than two decades on advisory committees, task forces, general plan committees, and other public bodies convened by City of San Rafael and/or the County to plan for these properties.

The earliest settlers of the land prior to about 1820 were Miwok. A large shell mound on the Silveira property and other evidences of early habitation suggest the presence of the largest intact Miwok village in Marin County. In 1844, Timothy Murphy (Don Timoteo) received the 22,000 acre Rancho San Pedro, Santa Margarita and Las Gallinas Mexican land grant and sold some of the acreage in 1845 to William Miller, whose family had pioneered the wagon trail through Emigrant Gap in the Sierra Nevada. He commenced a small dairy operation. In 1853 Murphy deeded 317 acres to Archibishop Alemany for education purposes. The eastern portions of the land were fully tidal until the Northwestern Pacific and Southern Pacific rail line was constructed. Toward the end of the 1800s, the land east of the railroad was diked off from the bay and drained for farming.

In 1900, Anthony Faustine Silveira, grandfather of the current owner, at the age of 14, purchased the Miller Ranch dairy business. Milk was shipped on the Northern Pacific Railroad from the Miller Depot Station to San Francisco for processing. He later built the Silveira family home in 1953, and purchased diked former tidelands east of the railroad tracks. Silveira Ranch currently leases about 11 acres of land to Marin County. Las Gallinas Valley Sanitary District, also east of the tracks, has provided wastewater treatment for northern San Rafael since 1955. Facilities include 390 acres for plant, habitat and storage ponds, and agricultural fields for spray irrigation of treated wastewater in the summer. Not counting the Sanitary District, the total acreage is about 1,200.

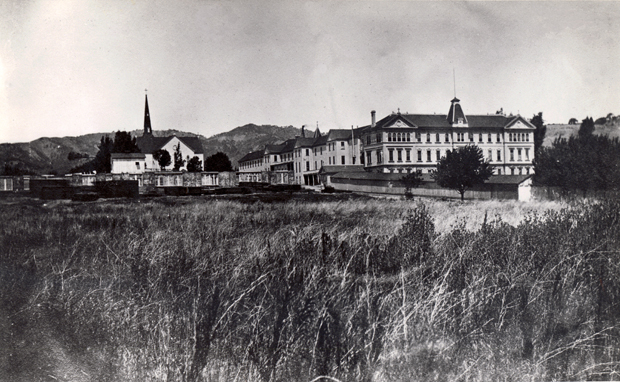

The St. Vincent’s Home and School for Boys was established in 1855 as an orphanage for children of the Gold Rush. The 40-acre school complex includes unreinforced masonry buildings dating from 1880 and 1911, but the majority of the campus was built in the 1920s, including the chapel. Still in operation as a school, the campus currently houses about 66 disadvantaged and troubled boys, aged seven to eighteen. The property is classified as a Calif. Historic Landmark #630 and is owned by the St. Vincent’s/Catholic Youth Organization.

St. Vincent's photo courtesy The Anne T. Kent California History Room,

Marin County Free Library

The two properties together form an ecologically significant transition between the bay and adjacent upland habitats. This part of the bay ecosystem has been lost throughout much of the San Francisco Bay Region, where levees and urban development most often meet the bay shoreline in an abrupt line, offering no refuge for wildlife during high tides nor the resources that overlapping habitats typically provide. The two properties also share natural features such as oak savanna and woodland, pastureland, riparian stream habitat, and oat-hay fields east of the railroad on diked baylands. Scattered small seasonal wetlands and drainage-ways occur on both properties. The Silveira property is crossed by Miller Creek, a major freshwater creek which becomes tidally influenced east of the railroad. A salt marsh has developed outside the levee along the edge of San Pablo Bay with the gradual accumulation of silt still circulating in the bay as a legacy of 19th century hydraulic mining in the Sierras. (This is no longer part of the site, having been deeded to State Lands Commission in exchange for quieting public trust claims over historic slough beds on St. Vincent’s diked former tidelands.) 144 bird and waterfowl species use the lands for all or part of their habitat needs, and the number of other vertebrate species is equally diverse.

Planning History

The planning history of these lands unfolds as a series of “chapters,” each revealing the controversies that have surrounded the properties for 50 years. The completion of the Hwy 101 freeway in the 1950s cleared the way for development of ranches to the west – Terra Linda, Marinwood, and Lucas Valley were all urbanized in the 1950s and 1960s. The Silveira brothers – Tony and Joe – elected not to sell their ranch east of 101. (A second Silveira Dairy Ranch lies north of Novato on both sides of 101). In 1965, the Williamson Act was passed, and Silveira Ranch entered into a contract that would reduce its tax assessment as agricultural land.

With adoption of the 1973 CWP and the three Corridors, however, the St. Vincent’s and Silveira properties found themselves in the City-centered Corridor. The County initiated termination of the contract, and by 1984, the Silveira Ranch was being taxed at market value based on its development potential. (St. Vincent’s, as church property, was exempt from property tax.) The updated 1982 CWP described the site as a study area having major potential for jobs and housing. The Plan also included a Bayfront Conservation Zone, which acknowledged the presence of ecological, geological, and other sensitivities of historic diked baylands such as those east of the railroad track but did not offer real protection from development. The Plan recommended a joint City (of San Rafael)-County planning process for St. Vincent’s/Silveira. From 1982-86, the County sponsored a study (North San Rafael Policy Plan) to designate what should occur there. This plan was never adopted because by 1986, Marin county jobs development had greatly exceeded expectations and conditions had changed.

As Marin County continued its transformation from a commuter suburb to a job-centered economy, traffic increased to gridlock conditions along the 101 corridor. Hamilton was in the process of planning for redevelopment; McInnis Parkway had been proposed; the 101 Corridor Study, which would lead to an unsuccessful tax measure in 1990, was underway. As one means of curbing further growth along Highway 101, attempts were made to keep the Silveira Ranch in permanent open space or agriculture through purchase. An article in the Marin IJ in 1989 reported that Supervisor Robert Roumiguiere was working on public purchase of 336-acre Silveira Ranch, which could cost between $20 and $60 million. The purchase would allow agricultural use of ranch to continue. The attempt was unsuccessful.

Purchase was not the only way to preserve agricultural land from development and from further congesting Hwy 101. An initiative to establish agricultural zoning was put before the voters of San Rafael in 1990. Measure L would amend the San Rafael General Plan to designate over 1,100 acres of land for agriculture. Three MCL committees reviewed the initiative before bringing it before the full MCL board, who heard arguments both for and against. The board voted in favor of the measure and actively supported it. In the general election, Measure L lost by a narrow margin. MCL then urged the City of San Rafael and Marin County to move aggressively with citizen participation to reevaluate the land use designation of the site to preserve its ecological, cultural, and open space values.

The two properties were within the City of San Rafael Sphere of Influence (SOI). To guide future planning for the site, the City appointed a joint 25-member City-County St. Vincent’s/Silveira Advisory Committee in 1991. MCL was represented. As part of the process, the City also held a design competition and received 77 entries that envisioned a wide array of possible plans for mixed development and preservation. The Advisory Committee completed its work in 1994 and submitted a majority recommendation that would allow up to 2,100 homes and 361,000 square feet of commercial development, as then reflected in San Rafael’s General Plan 2000. The report was not unanimous, however. A minority report was also submitted that called for no development of the Silveira lands and limited development (five percent of the total land) and reuse of the St. Vincent’s buildings, to be accomplished through public acquisition of the Silveira lands and transfer of development rights between the two properties. The minority report also recommended that neither of the two properties be annexed to San Rafael and that all planning functions remain with the County. These conditions – very limited development, public acquisition and/or transfer of development rights, and county jurisdiction – would frame the MCL position for years to come.

Dairy cows at Silveira Ranch with St. Vincents in the background, taken from the McInnis Skate Park. The structures on the right are the old County Honor Farm, currently the site of a drug and alcohol abuse treatment center, and soson to be the new headquarters of the animal welfare group, WildCare.

Dairy cows at Silveira Ranch with St. Vincents in the background, taken from the McInnis Skate Park. The structures on the right are the old County Honor Farm, currently the site of a drug and alcohol abuse treatment center, and soson to be the new headquarters of the animal welfare group, WildCare.

As both City and the County were about to embark on major general plan updates, they entered into a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to share planning authority for both properties. A 14-member Task Force was convened, including three environmental representatives, two from MCL and one from the agricultural community. Again the intent was to reach a community consensus on the future disposition of these lands. In an attempt to reassure environmentalists, the City and county agreed on a significant reduction in total development, no rail station at St. Vincent’s, and allocation of a possible $55 million for purchase of lands for open space, should a future transportation tax measure (including rail) be successful. The Task force began its work in September 1998 and after a heavily facilitated process, made their recommendations in 2000. The recommended range of between 500 and 1,800 residences sent a strong signal that the Task Force had not reached real consensus. The environmental representatives at first agreed to the lower level, but when the outcome appeared headed toward the higher number, they repudiated the report. The MCL board closely monitored the Task Force for 20 months, consistently arguing that the fundamental premise of the MOU – that an “urban neighborhood” of San Rafael be developed on the site – was flawed: that level of development would be wholly inappropriate given the constraints.

The political winds changed dramatically in 2003 with the election of Susan Adams to the Board of Supervisors. Adams ran on a platform of little or no development at St. Vincent’s and Silveira Ranch. St.Vincent’s had by this time submitted an application and was working with San Rafael on plans for residential and commercial development on their land, as well as a new school campus to be built east of the tracks. Almost immediately on Adams' election, San Rafael, recognizing that a collaboration with the County on the properties might be contentious, initiated proceedings to terminate the current planning process and remove the properties from the City’s SOI and Urban Service Area. All future land use determinations for the properties thus would go to County of Marin. St. Vincent’s (Catholic Youth Organization) sued the City, but ultimately the City prevailed.

The most recent chapter, but not the last, coincides with the updating of the CWP, which began in 2001 and was approved in late 2007. Foremost on MCL’s agenda was inclusion in the revised CWP of a Baylands Protection Corridor that would encompass all of the St. Vincent’s and Silveira Ranch properties in addition to other diked former tidelands in Marin county. This would dictate how much development could occur and where. After lengthy debates before both Planning Commission and BOS, the Baylands Corridor did become the “fourth” corridor in the Plan. A more compelling factor influencing acceptable level of development, however, was the limited capacity of the Hwy 101 corridor to accommodate more traffic. In that regard, it was finally determined that development at St. Vincent’s/Silveira that generated no more new traffic than would result from 221 dwelling units would be allowed. A more likely development with broad acceptability would be an institutional use, such as a senior living facility.